DIASPORA

EXPRESSIONS

ON SPIRITUALITY & RITUAL

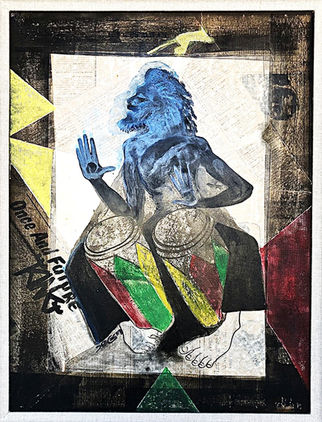

Ademola Olugebefola • USVI

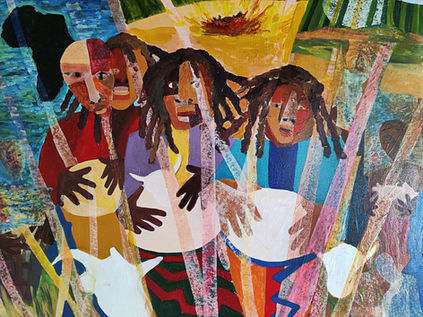

Arlette St. Hill • Barbados

Bernard Stanley Hoyes • Jamaica

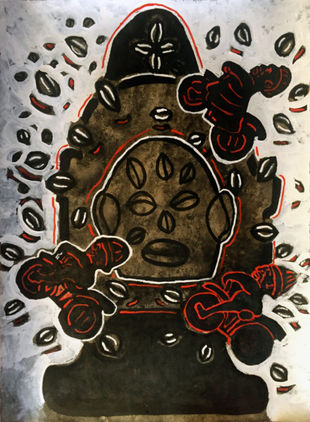

Diogenes Ballester • Puerto Rico

Earl D. Etienne • Dominica

Patricia Brintle • Haiti

Curated by Anderson Pilgrim

A message from the Curator

As African people were scattered across the New World during the Middle Passage and 400 years of human trade, so too were many of their cultural practices, modes of worship, and rituals surrounding life moments. These ancestral elements manifest themselves in religious movements, cultural expressions such as dance, visual arts, and carnival arts, many of which have entered the mainstream, while some others have been maligned in popular culture. Growing up in the Caribbean, I would venture to say that most of my contemporaries and I were taught to disavow the practices of Vodou/Santeria/Obeah in whichever island we lived.…”Black magic” they called it. How ironic. However, there is a movement among contemporary practitioners, in the Americas especially, to try and dispel those misconceptions and reclaim the public narrative about the religion. In a recent article in The Atlantic (June 2022) entitled, “The Black Religion That’s Been Maligned for Centuries”, Haitian American environmental educator Alain Pierre Louis says, “Vodou is very big on respecting nature, remembering the ancestors, and the rhythm and vibration through dance, song, and the drum. Vodou is energy.”

The artists featured in this exhibition have made a practice of exploring various aspects of this ethereal energy which manifests itself throughout the African Diaspora. Arlette St. Hill and Bernard Stanley Hoyes both capture those elements of spirituality which express themselves through dance, song, and the drum. The rituals of the various Spiritual Baptist sects in the English-speaking Caribbean are of particular interest.

Ademola Olugebefola and Diogenes Ballester each powerfully fuse disparate ancestral symbols into their own unique visual language.

The late Earl Etienne celebrates the ubiquitous Sensay character which has become an integral element of so many Caribbean carnivals across the Americas. His “Kibuli Dancers” depicts all the rhythm and vibration of that ancestral energy. Patricia Brintle explores a level of syncretism between mainstream religion and the deities of traditional Diaspora practice.

I am pleased to present their explorations and vision in partnership with the Caribbean Museum Center for the Arts. Enjoy the experience.

Anderson M. Pilgrim

Caribbean Religion, Art, Spirituality and Ritual

Essay by Carol B. Duncan, PhD

Department of Religion and Culture

Wilfrid Laurier University

Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

Modern Caribbean history was deeply shaped by Western European imperialism and colonization which began with the late fifteenth century expropriation of Indigenous peoples’ lands, and the practice of various forms of forced migration and labour, including broadscale enslavement of Africans, in the cultivation of sugar and its byproducts for the global market. Colonization was a militarized process of political and economic domination that was also fostered by cultural and symbolic coercion which included religion, in this instance, Christianity and the incursion of Western European languages.

Enslaved Africans, indentured and other subjugated peoples and their descendants resisted with individual acts such as petit marronage and collective acts such as grand marronage and rebellion. Artistic expression and religion are intrinsic components of Caribbean expressive cultures and a crucial part of the cultures of resistance. With a colonial legacy of centuries of exclusion from formal recognition as legitimate artistic expression, visual artistic expression in the form of sculpture, painting, photography, needlecraft and other media nevertheless emerged and thrived.

The role of the artist is crucial in representing ritual. The design of altars, production of items used for rituals in religious and spiritual contexts such as drums and garments underscore the link between artistic expression and ritual practices. As described by ritual studies scholar Catherine Bell, ritual is a form of “enacted thought” (Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice, 1992).

Caribbean religion and more broadly, spirituality, encompasses a variety of faith traditions, beliefs, worldviews and ritual practices. There is no singular Caribbean religion or understanding of ritual and its significance. Instead, the term “Caribbean religion” is shorthand to describe traditions created by enslaved Africans, the indentured and their descendants. Religion here is understood as engaging not only belief systems but what people do in sacred spaces and in their everyday lives (Malory Nye, Religion, the basics, 2nd edition, 2008). These traditions emerged out of resistance to enslavement, indentureship and colonization which has characterized the region, historically, since the earliest days of Western European empire building from the late fifteenth century. For example, traditions such as Haitian vodun, Cuban santería and espiritismo emerged out of the continuity of African traditions and reinterpretations of forms of Euro-American Christianity as explanatory frameworks, systems of healing and powerful ideological support in engaging the predicament of enslaved, indentured and colonized people.

Similarly, in the English-speaking Caribbean, Rastafari, Spiritual Baptists and Jamaican Native Baptists interpreted Euro-American Christianity in ways that positively supported authentic African and diasporic African identities, communitarian values and resistance to subjugation. Subjected to colonial repression and control by law and custom over the centuries, these traditions nevertheless survived and flourished meeting the religious, social and spiritual needs of their individual practitioners and their communities. They were, and continue to be, living repositories of culture in which linguistic, musical, dance, drumming and visual artistic traditions which have survived and thrived. The development of carnival mas’ (masquerade) traditions is a prominent example in which these elements are visibly, orally and aurally present as expressions of Caribbean peoples’ worldview and aesthetic cultures. As cultural anthropologist Solimar Otero noted in Archives of Conjure (2021) such practices represent “archival spiritual knowledge.” Artists are important contributors to these archives.